- Home

- Zoe Pilger

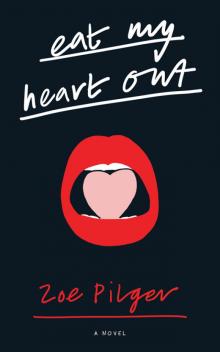

Eat My Heart Out

Eat My Heart Out Read online

Zoe Pilger is an art critic for the Independent and winner of the 2011 Frieze International Writer’s Prize. She is currently working on a PhD at Goldsmiths College and lives in London. Eat My Heart Out is her first novel.

Eat My Heart Out

Zoe Pilger

A complete catalogue record for this book can be obtained from the British Library on request

The right of Zoe Pilger to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Copyright © 2014 Zoe Pilger

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, dead or alive, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher

First published in 2014 by Serpent’s Tail,

an imprint of Profile Books Ltd

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

London EC1R 0JH

www.serpentstail.com

eISBN 978 1 84765 971 2

For Joe Silk

1977–2003

Too bad

I’m not stronger. I’d be worse.

Ariana Reines, Coeur de Lion

One

The sky was still black when the butchers began unloading the pigs from their vans at Smithfield Market. It was five in the morning. I had been to a party nearby. There he was, loitering across the road. He was watching the meat with terror and awe.

His black hair was lank, and, as I approached, I could see that a military medal of some kind was pinned to his beige crochet jumper. He was freakishly tall, about six foot seven. He wore a red hat and he was shaking with cold.

‘Hi,’ I said. ‘I’m Ann-Marie. I’m twenty-three. How old are you?’

He seemed shocked that I was talking to him. ‘Thirty-six.’

‘That’s a good age.’ I shoved my hands deeper into my vintage structured tweed and asked him if he wanted to go for a coffee. ‘Maybe we’ve got something in common,’ I suggested.

‘I doubt it.’

‘I adopt loads of pussies from a refuge,’ I said. ‘Yeah, and I love to feed the pussies condensed milk in tiny china dishes. I lounge around on my chaise longue in my red silk kimono and I watch their pink tongues lap it up.’ I paused for effect. ‘They love to lap it up.’

Vic gave me his email address.

That was yesterday.

Dear Vic,

It was lovely to meet you!

What are you up to later?

I’ll come to where you are.

Ann-Marie X

Today I was waiting at the window on the first floor of a waxing salon across the road from Chalk Farm tube station, where Vic had chosen to meet. The manager had told me that they were nearly closing, but I’d made my eyes look beseeching like a spaniel and the drowned aesthetic must have helped because she let me in. I could hear a pan-pipe rendition of ‘These Boots Are Made for Walkin’’ emitting from a closed door; I could smell the floral notes of wax. I waited.

And waited.

To wait is a woman’s prerogative, according to Stephanie Haight, whose book Falling Out of Fate had recently been shortlisted for the Samuel Johnson Prize for Non-Fiction. To wait is a woman’s raison d’être. To wait and see what a man will do for you. Do to you. I hadn’t bought the book yet because I had no money, but I’d heard her speak on Start the Week. Her accent had a twang; I couldn’t tell if she was American or English. Waiting for the call, she’d said. Waiting for that fateful ring of the telephone situates woman in a passive position. It is akin to waiting for The Call from God.

November commuters were rushing away from the station in the street below. The rain was torrential; it obscured the stars. There was no one I recognised.

The waxing woman was trudging up the stairs behind me when at last I glimpsed that red woolly hat. ‘Have you seen enough?’ she was saying.

I watched Vic cross the road.

Now the woman had a hand on my shoulder. She turned me round.

‘Do you mind if I wait here for just a few moments longer?’ I said.

She returned downstairs so that I was alone again with that music, which had changed to ‘My Heart Will Go On’. Vic was wearing a red anorak. He didn’t smoke a cigarette; he didn’t look at his watch. He reminded me of a Giacometti: emaciated by the act of living.

I rooted around in my handbag for Heidegger: An Intro and read: Concept of Thrown-ness: One is thrown into the world and one must deal with it. I closed the book. Since I went crazy during my university finals a few months ago, I could only read these terrible comic-style philosophy manuals, and only one or two sentences at a time.

Now Vic was circling a lamp-post.

A door on the right of the corridor opened and a woman appeared with the blank face of one who has just been tortured. Another woman in a white apron followed her. There was an intense smell of sugar – no, cocoa butter. The blank woman was about forty-five, but she was saying in a little girl voice: ‘Thank you ever so much. I do feel so much better now. It’s my anniversary.’ They disappeared without looking at me.

Now Vic was holding onto the lamp-post and looking up into its light, letting the rain fall on his face.

Ten minutes had passed.

Soon he would go.

Would he go?

I watched him reach upwards to the void of sky; he seemed to plead with it. And then he was going, taking long strides with his gloopy, elastic legs, splashing through puddles that reflected cars and red light. He was leaving, he was leaving.

The music had stopped.

I ran down the stairs and across the street. I had lost sight of him; Him. I wanted Him more now, much more, since He was already leaving me.

I found the red hat striding over the bridge towards Primrose Hill. I got close enough to watch the rivulets of water running down Vic’s plastic-covered back. I fell into step behind him. The black heavens never answered my questions. Why not?

I pounced.

I got my arms and legs around him, piggy-back style. He grunted, a stuck pig. He tried to push me off, but I clung and clung and clung. Stephanie Haight had said that that is what women are wont to do.

We fell, together.

I whispered into his ear: ‘Hello Vic, it’s very nice to see you again. Sorry I’m late.’ I paused. ‘This seems like a good moment to lay my cards on the table. You’re my first date since I got out of a really long-term relationship.’

We were flat-out on the pavement. People were walking around us, but no one stopped to help. Vic sat up and touched his forehead. He was bleeding.

I went on: ‘My ex-boyfriend Sebastian was fucking this girl from the Home Counties called Allegra behind my back. I didn’t think I’d ever get over it, but now – since I’ve seen your face, I think I might get over it.’

The lights of the fruit machine whirred in the corner, spinning their pictures of apples and bananas as I sipped my large glass of house white wine and tried to seem engrossed in Vic’s pronouncements on operation management.

‘So you manage the operators?’ I said.

‘Not exactly. I operate and I manage. I live with other operators who are lower down the pecking order than me, but I don’t let that affect things like who can use how much space in the fridge.’ He shrugged.

A large bull-fighting poster was framed on the wall to his left. It showed a blindfolded horse being gored by a bull. A matador stood poised to stab the bull with the final sword. We were squeezed onto the end of a table of graphic designers, who had offered to

drive Vic to the hospital for stitches because the gash on his forehead continued to bleed.

‘At least you didn’t break your nose,’ I said. ‘My friend Freddie who I live with has got a broken nose. And he’s got these eyes like a fawn about to be shot. The juxtaposition is quite poetic.’

‘Do you always use long words?’ said Vic.

‘I’m not an elitist.’

‘I’m an elite,’ he said. ‘I’m a one-man elite. That’s the way it is in the services.’ There was no sign of the medal that he had worn yesterday.

‘So you were in the army?’ I said. ‘That must have been what drew me to you. Did you like get discharged for gross misconduct or something?’

His face looked pained for a moment and then it hardened. ‘No.’ He leaned forward. ‘You know, you’re lucky that I’m here with you, that I’m willing to fuck you still, since you gave me concussion.’ He touched his wound.

I pulled his hand down. ‘Don’t, Vic. It might get infected.’

‘I would like to infect you,’ he said, heartily. ‘Posh girls like you want to get infected by a real man like me.’

I sighed. ‘Real men are hard to find.’

‘That’s because all you castrating bitches don’t know your place any more.’

There was a long silence.

‘I went to Cambridge,’ I said. ‘Yes, that’s right. The real Cambridge. Not the ex-polytechnic. So it’s a curse and a blessing in a way because when one elevates oneself above the quotidian, one starts feeling terribly lonesome, as though one will never find a soulmate again.’ I paused. ‘I guess Freddie is my soulmate now.’

‘Do you like the way he fucks you?’

‘He’s gay.’

I felt Vic’s hand grope my thigh under the table. We were sitting quite far apart; his arms were as long as an ape’s. I moved my thigh away and his hand thudded to the ground.

‘Fine,’ he said.

I downed my drink. ‘Shall we get another?’

‘Great.’ He leaned back. ‘Thanks.’

The song changed to Curtis Mayfield’s ‘Move On Up’. The graphic designers started dancing in their chairs.

‘But I got the last one, Vic.’ I wanted to cry – maybe he didn’t love me?

‘Only joking, only joking.’ He laughed. ‘Shall I get a bottle?’

The next thing I knew I was riding Vic hard in the back of a taxi, muttering into his mouth: ‘Fuck me right here, right now. Tell me what you want.’

‘I want you to get off,’ he was saying. ‘Get off.’

‘No, no, no.’ I slapped his face. ‘Isn’t that the word you like to hear from women?’

‘No,’ said Vic.

I got off and slid as far away from him as possible.

The taxi slowed with the traffic on Chalk Farm Road. A woman wearing a white wife-beater and a pair of acid-wash dungarees despite the harrowing cold was crawling on all fours outside the kebab shop, picking up the remains of her chips and cheese and cramming them into her mouth. We drove on, slowly. A gang of girls were swaying together in a long link-armed line over the lock, singing some mournful song: ‘The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face’.

I wound down the window and leaned my head out. ‘That was my parents’ song!’ I shouted. I turned to Vic: ‘That can’t be a coincidence?!’

One of the girls broke away from the chain and sprinted in six-inch neon green heels towards the dark window of a leatherwear shop. She lowered her head like a bull, laughing all the way. Her friends grabbed her arms just before her head smashed into the glass. She fell back into them, laughing harder.

‘Close the window!’ shouted the driver.

I did.

London is a depressing place to look for things.

The doors on the first floor of Vic’s house were all white and all shut. I’d stripped off my clothes downstairs and now I was throwing my naked body against each door in turn. They stayed shut – locked? Vic was mumbling about not waking the operators. He was picking up my clothes.

‘Fuck me,’ I was saying. ‘Fuck me, fuck me, fuck me.’

Finally he produced a key from his pocket and opened a door on the left. ‘We like our privacy,’ he explained. ‘Security is always an issue. Even among friends.’

He followed me into the dark room. I hit my shin on the bed. Vic turned on the light. It was a futon. A NATO aerial bombardment map was pinned above the mirror. There was a poster of the film Taxi Driver. The room was monkish, the perfect place to ask for forgiveness.

Vic was surprised when I rolled away from his hairy body and produced a packet of Performa condoms from my handbag. I snapped one on his penis efficiently.

It immediately began to die.

‘Would you rather we didn’t use them?’ I said.

‘Yeah. Thanks. It’s just that I don’t like the sensation of condoms.’

‘Well, I don’t really like the sensation of abortions.’ I sat up. ‘I don’t really feel like having a foetus ripped out of my womb, thank you very much.’

There was silence.

I felt for it, but now it was dead.

He got out of bed and stood over me. ‘Why do you humiliate me?’

I waited.

‘Hit me, then,’ I said.

He exhaled, agonised. He lay down again.

Soon he was snoring.

I moved into the crook of his arm. I felt so happy then.

The dawn entered the room. I rolled over and lit a cigarette. I tried to hold onto Vic, but he was pushing me off in his sleep. His head injury had scabbed. Experimentally, I ground the cigarette into his chest.

He woke up, screaming. ‘What the fuck are you doing?’

I rubbed the cigarette out between my fingers.

Now the room was ablaze with morning.

‘Do you love me?’ I said. ‘Now that we’ve had sex?’

He pretended to sleep again.

Finally he mumbled: ‘We didn’t have sex.’

‘But do you love me anyway though? Because we might have sex in the future?’

He sat up. ‘What about the pussies from the refuge?’ His face looked dire in the light. ‘What about the red silk kimono? Who are you?’

‘Yeah, I’m not in the habit of going out in nightwear. I do own one though. Freddie’s always trying to borrow it.’

‘You know it’s really off-putting for a girl to keep on going on about her ex-boyfriend on a first date.’

‘Freddie’s not my ex-boyfriend, I told you. And this isn’t our first date, Vic. We met in a past life. I was your faithful concubine. But now I’m an empowered woman.’ I corrected myself: ‘I’m a woman in the process of becoming empowered.’ I laughed. ‘If you’ll only let me.’

Vic lay down again.

I rolled another cigarette.

‘No,’ he said, and tossed it somewhere. ‘You’re desperate.’

I laughed. ‘No, Vic. That’s the trouble. I think I’m desperate, I even want to be desperate, but I’m not. The sad truth is that I’m not. Maybe if I was, then you’d love me.’ I stood up, exhilarated. ‘But I’m not.’

I got dressed quickly.

‘You’re all the same,’ he mumbled, face down in the pillow.

The front hall was adorned with black and white photographs of Big Ben, captured from a range of surreal angles. This was a terraced house. I could hear operators talking in the kitchen. I went in.

There was a breakfast bar. Operators – two men and a woman – were sitting around it on matching stools. There was a laptop. On the screen, there was a picture of marmalade on toast. A real piece of half-eaten toast was spotlit on the counter.

‘Yeah,’ the woman was saying. She had brown hair, and no distinguishing features whatsoever. ‘And put the date and time. And say what it is.’

‘What is it?’ said the man, fingers poised over the keyboard.

‘Toast,’ said the woman.

‘Hi!’ I said. ‘I’m Ann-Marie! Vic’s new friend.’

The

y stared at me.

There was an empty stool – Vic’s? I perched on it, taking a bite out of the toast, nodding with approval. I could see that the marmalade on the screen was a more brilliant shade of amber. It had been photoshopped.

‘I’ll probably be hanging round here a whole lot more from now on,’ I said.

They continued to stare.

The woman plunged a cafetiere. They didn’t offer me any coffee.

‘Vic told me what happened in the army,’ I lied. ‘It’s terrible. I’m really hungover. We got totally trashed. I don’t usually get this trashed any more, not since I went on this mad detox diet for the six months leading up to my finals.’ I nodded. ‘I just graduated. I got a double-starred first actually, from Cambridge.’

They didn’t look impressed.

‘My director of studies, Dr Kyle, said that I could easily win a scholarship to Harvard or some other Ivy League place,’ I said. ‘Maybe a more progressive one, but I said I just want to be free, you know? Like now.’ I finished off the toast. My voice sounded dead: ‘I’m free.’ I got off the stool. ‘Well, um. I better … go to work.’

‘Vic never talks about what happened,’ said the woman. ‘It’s dangerous for him to talk about it. It triggers things.’ She looked at one of the men. ‘I told him he shouldn’t hang around that meat market. Why seek out what you’re most afraid of?’ She held the fridge door open. ‘Vic is terrified of meat.’

‘Oh?’

‘Yeah,’ said one of the men. ‘Ever since the accident in the woods when he was in the army, he can’t go near it. The doctor told him not to go near it.’

‘I can empathise with that though,’ I said. ‘I only ever want what I hate.’

‘Well, you’re special.’ She pulled out some raspberries and closed the fridge.

I was about to leave and never come back, but then I changed my mind and ran upstairs. I tried every door before I got the right one. There he was, a corpse. I got out my notebook. I thought about writing him a love poem.

‘Vic?’ I knelt beside him. ‘What did you do? What happened in the woods?’

Nothing.

‘Did you kill someone?’

Eat My Heart Out

Eat My Heart Out