- Home

- Zoe Pilger

Eat My Heart Out Page 18

Eat My Heart Out Read online

Page 18

Hal began to strum his guitar again so that we had to shout louder over the music. His song was rambling and tuneless.

‘And playing the Hooray Henry,’ Sebastian’s father went on. ‘Going punting in that godforsaken boater. Going to formal halls, when you didn’t even belong to a college.’

Fifteen

Abreaction: A Novel

Chapter 1

Sisyphus was named as such because her parents intimated from her startling hazel eyes that she was doomed to roll a rock up to the top of a hill, only to have it roll down again, so that she would have to roll it up again, and so on, for all eternity.

They would have her believe that her fate was inscribed in her name.

When Sisyphus won a scholarship to St Anne’s College, Oxford, she was ecstatic. She surmised that there was no need to hold a pillow down over her well-meaning parents’ faces as they slept because now she was free.

She had fallen twice thus far.

The first boy she fell in love with was a local gangster called Simon. He was born of Chinese descent but his parents anglicised his name. He wore a diamond in his ear and he starred in black and white TV ads for oriental-style noodles. It was a time when Chinese cuisine had barely entered the UK.

All the girls loved Simon. Sisyphus knew she would never get him because she was so morbidly obese. He was subject to much racism from the teachers and she longed to position her whale-like body in front of him in the form of a human shield, but he bullied her along with the rest. It was then that she came to understand the veracity of the Auden line: ‘Those to whom evil is done / Do evil in return.’

She prayed to the moon that Simon would love her back. She devised superstitions, wishing for particular patterns of numbers to occur. Soon, she became a slave to those patterns. They ruled her with a logic that she herself had created.

The moon’s face remained impassive outside her bedroom window. Simon continued to appear in flickering black and white on the screen, and sometimes in the form of a jingle on the radio. Sometimes she doubted that Simon was real at all.

On the upside, she discovered a mystical inner world. Her desire for him was celestial, not sexual. It belonged to the stars; stars exploded within her. He seemed to be the most powerful person in the universe. He was the sun around which she revolved, just like the songs said it should be. But if he didn’t exist then maybe her circular path had no centre?

Her second love was called Billy. He fell in love with Sisyphus because she was assertive, like a man. She bulldozed people on the way home from school like a man. And if he closed his eyes, he could just about imagine that she was in fact a man.

Billy had fantasies of being tied to a lamp-post and beaten by Sisyphus. While researching her thesis on romantic masochism in the work of Simone de Beauvoir years later, Sisyphus would come to realise that Billy had been using her as a way of punishing himself for his own illicit homosexual desires. He wouldn’t come out of the closet until he was married with two children.

Billy made her the aggressor in the relationship. She felt herself to be an aggressor in any case because she was always compelled to defend herself. She was angry as hell. She was defensive as hell. She had to be. It’s called survival. She would fight and fight and fight, and Billy would whimper and cry. She would wish that he was a real man, a macho man, but then all the macho men ridiculed her mercilessly. They wanted childlike girls, who had no ambitions of their own.

Sisyphus had nothing but her ambition. She allowed Billy to make her orgasm from behind but all the time she was plotting her escape from her family and his terrible silhouette cast on the wall of his father’s shed. That’s how she knew she didn’t love him: she abhorred his silhouette.

Years later, when her head was bent over the tomes in the Robbins Library, Harvard, she would realise that both Simon and Billy had been mere pretexts for her to seethe with a solipsistic passion. It was a private passion, upon which they could not trespass.

On an unconscious level, she had ensured in both cases that reciprocity was impossible. She loved Simon; he didn’t love her. Billy loved her, but she didn’t love him. He only loved her because he was lying to himself and the rest of society.

Someone was always turning away. But did it have to be so?

The rock which Sisyphus rolled up her hill would soon become heavier still. Indeed, soon the hill would turn to ice. The surface would become so slippery that rolling the rock would be nigh on impossible. She would meet Leo, an extraordinary American ice hockey player.

I read Steph’s novel on the night bus headed towards Camden Square. I didn’t want to stay in Sebastian’s bed after that furore. And I couldn’t be sure that the crazy woman had cleaned all the shit off my bedroom walls in Clapham yet.

Stephanie promised to reinstate her cleaner, Ilka. She promised that there would be no more sadism, no more chores. She said she loved me, and that without me, she was nothing. She said all this in a stream of consciousness while Marge stirred and stirred that damn chicken soup for the soul, made with my halal.

Raegan was the only one I was happy to see.

There was a hamper of Harrods bespoke offal on my bed. It had been there for some time; it was rotting. The urinal scent of kidneys overwhelmed the Florida Water.

There was a note:

MA CHERIE CAMILLE,

DID YOU RECEIVE THE GARTER? OH, HOW I DRIVE MYSELF TO THE POINT OF DEMENTIA OF A NIGHT IMAGINING YOU SLIPPING THAT ELASTIC OVER YOUR LITHE THIGH. I IMAGINE SINKING MY SORROWFUL TEETH INTO THAT THIGH. SORROWFUL BECAUSE YOU DO NOT WRITE, YOU DO NOT CALL. DO YOU THINK OF ME? CAN I HOPE THAT YOU DO?

OUR NIGHT TOGETHER WAS INCENDIARY. INCINERATE ME AGAIN, MY PRECIOUS ONE. LET ME INCINERATE YOU. JOUISSANCE COMES IN CLOUDS ACROSS MY VISION AND I CAN’T THINK, AND I CAN’T SEE. I YEARN TO TAKE YOU UP TO THE CHARTREUSE MOUNTAINS AND SAMPLE THAT MONKISH BLUE LIQUEUR. OH, HOW WE WOULD SCANDALISE THEM! I YEARN TO MAKE THE FATHERS DISAVOW THEIR FAITH AND THEIR GUILT. THEY WOULD, AFTER ONE LOOK AT YOUR SILKEN SKIN.

YOU HAVE BROUGHT OUT MY PLAYFUL SIDE! I WANT TO SEE YOU IN THE WHITE OF MISS H BEFORE SHE STOPPED ALL THE CLOCKS AND LET THE RATS GNAW AT HER CAKE. WILL YOU WEAR HER DRESS FOR ME?

SALUD,

JAMES X

I had taken Stephanie at her word that she would give me anything I wanted so the following morning we went to Selfridge’s. I wanted to buy a new outfit for the Samuel Johnson Prize that evening. It was Friday.

The personal shopper was throwing Oscar-style gowns at me: a yellow satin Cavalli, a bustier McQueen printed with dragonflies. Finally, I settled for a Lanvin contrast silk. The front was black and the back was red. It cost £2,320.

‘Are you sure you don’t mind?’ I asked Stephanie, when we were seated at HIX Champagne & Caviar Bar on the fourth floor. I had already disposed of the receipt for the dress in the ashtray outside.

‘Sure.’

‘I mean I’m gonna need shoes to go with it,’ I said, my mouth full of osetra caviar and hot buttered toast. ‘Can’t wear these.’ I gestured to my old door bitch ballet pumps.

Her phone rang. ‘Yes,’ she said. ‘Yes. Yes, of course she will. Protected? No problem. Thanks, Francesca.’

‘Who’s Francesca?’ I said, when she got off the phone.

‘She’s a researcher on Woman’s Hour. They heard about your (un)authored blank page from the MD of Mental. They want to run an item on it.’ She tried to look excited. ‘They want you on the show!’

‘Excuse me,’ I said, gesturing to a waiter. ‘Can I have …’ I checked the menu. ‘The white duck egg with the osetra again. Thanks.’

‘This will be great for your profile,’ she said.

‘I don’t want a profile. Do you mind if I go outside for a cigarette?’

‘I am trying to help you, Ann-Marie.’ Steph wasn’t eating. ‘I wouldn’t even be going to this phoney awards ceremony tonight if you didn’t want to go.’

‘But your book might win.’

‘Me or that

awfully boring history of Elizabethan ceruse. Like a man could understand the historical significance of a cosmetic that causes death by lead poisoning.’ Steph snorted. She tugged at her straw-blonde hair. ‘Well, do you want to go on Woman’s Hour or don’t you?’

The duck egg arrived.

‘What’s my fee?’ I said.

‘Victims don’t get a fee just for being victims. That’s not how it works.’

‘How does it work, Stephanie?’ I pulled out Abreaction and flipped through it. ‘I’m looking forward to finding out what Sisyphus did to Raegan and Marge.’

She took the book out of my hands and put it on the table. ‘You’ll need a bag too,’ she said. ‘I spotted an adorable Mulberry spongy leather medium hobo that you could use day to day. Not just for tonight. Not just for tonight.’ Her eyes returned to the Erzulie state. Then she smiled briskly and said: ‘I know what! We’ll call on Gabriella on the way to the BBC! That’ll be wonderful for you, won’t it?’

Gabriella’s studio was in London Fields.

Hipsters wearing white surgical masks and gowns were bent over what looked like a corpse. Its flesh-coloured feet were protruding from one end of the operating table. The studio was huge and white with compartments everywhere. Images of operations were propped on shelves. One face recurred: that of a woman turned yellow by the antiseptic fluid wiped across her skin, turned yellower still by the bruises left by incisions. Here, her eye was cut open, the iris a technicolour blue. Here, her breast was removed, leaving a textured red mess. Here, her breast had been appliquéd back on, the stitches made of hot-pink wool.

One of the masked hipsters made a big fuss of Stephanie, who strode over to the corpse and demanded: ‘Gabriella? Gabriella? Is she under?’

The hipster pulled the sheet away from the corpse’s face to reveal a hyper-real fibreglass dummy. Its eyes were that same technicolour blue. I tried to get a look at the gaping wound on which the hipsters were working and saw that there was yet another fibreglass dummy tucked inside the stomach. The second, smaller dummy was likewise being operated on. There was yet another dummy inside of her, inside of her. The dummies got smaller and smaller so that the last was no bigger than a finger.

‘It’s called The Russian Within,’ said the hipster. ‘It’s a comment on Anna Karenina. And like, Russian dolls.’

‘Where is she?’ said Stephanie.

The hipster led us through another studio where something was being blowtorched. It was obscured by a sheet.

‘Gabriella was always interdisciplinary,’ Stephanie said.

We entered an office.

Gabriella was slouched behind a large white desk. ‘Tell them I don’t care about the cost,’ she was saying down the phone. ‘I want ostrich. It’s the soft – yes, the soft. And the fire in the grate and the ice in the glass. I want a lot of ice in the glass and I want the glass to be very big. And I want lizards – two, maybe three, crawling up the wall. I want the walls to move. No – I don’t want the walls to actually move, I want the lizards to make the walls seem like they’re – yes.’ She had been doodling a lizard on a pad. Now she looked up. ‘Etienne,’ she said. ‘I have to go.’ She opened her arms wide to Stephanie. ‘Mum.’

‘I wish you wouldn’t call me that,’ said Steph.

‘You love it,’ said Gabriella, lighting a cigarette.

Steph lit up too.

So did I.

We all three stood in silence, smoking.

I tried not to stare at Gabriella.

She was a spectre. Her skin showed no sign that anyone lived inside it. Everything on the outside had been changed. She looked like a 3D dragon touched by the old-world glamour of Elizabeth Taylor. Her cheekbones were like rocks, her lips like wet, full slugs. She was dressed like a French provincial housewife, but her accent was English.

When we had all finished our cigarettes, Gabriella said: ‘And is this your new daughter?’

‘She’s a friend,’ said Steph.

‘Oh, we’re all friends,’ laughed Gabriella.

Her eyes were the same technicolour blue as the eyes in the photos. Was she wearing contacts?

‘And what are you doing here, Mummy?’ Gabriella asked Steph.

‘I thought you might like to tell Ann-Marie all about your beginnings!’ Steph turned to me. ‘Gabriella has got a midcareer survey coming up at MOMA. She’s doing just great.’

‘Yeah, I’m great,’ said Gabriella. ‘My beginnings? Wow. OK.’ She hobbled over to a filing cabinet. Her legs seemed to be fitted at awkward angles to her upper body. She selected a white folder. ‘At first, I was looking for something,’ she said.

‘You see?’ Steph turned to me. ‘We’re all looking for something!’

‘But I was looking for something real,’ said Gabriella. ‘The Lacanian Real, more precisely – which isn’t real, of course. But The Unnameable darkness. And all the more powerful for it.’ She sat down on the edge of the desk and winced. ‘Something that I could feel, in any case. Not some bullshit quasi-spiritual mantra in India. Like Marge Perez. Patronising the shit out of the Indians.’ She opened the folder and tossed a handful of stills on the desk. ‘This was the King Cake project. My first art installation. 1993.’

The image showed a much younger, plumper, and more natural Gabriella prone and naked and covered in what looked like icing.

‘Explain how you did it, Gabriella,’ said Steph.

‘Yes, Mum.’ Gabriella laughed. ‘The King Cake is a cake that is traditionally eaten in countries all over the world, from Spain to Lebanon. They bake a little figurine of a king – more precisely, a baby Jesus – in a cake and then slice it up and eat it on the sixth of January. That happens to be my birthday. Whoever finds the figurine in their slice is lucky but also runs the risk of breaking a tooth. It’s also known as the Epiphany Cake, and sometimes, the thing in the cake is a bean, not a Jesus.’

The second image showed a carving knife looming towards Gabriella from the left.

‘Go on,’ said Steph.

‘So I just took that idea and ran with it,’ said Gabriella. ‘I was the cake. There was a thing – like a little figurine, a king, a father – inside of me and I wanted to find it.’

‘So you … swallowed a figurine?’ I said.

‘No. The figurine was a metaphor, only. It was The Unrepresentable. Trauma. It was ephemeral, impossible to pin down. That’s why I wanted to pin it down. To persecute it. I pinned myself down in the process, since it was a part of me. I didn’t know where it was inside of me exactly, but I wanted to cut it out. I was prepared to cut my whole self to pieces trying to get it out.’

‘That’s abreaction,’ said Steph.

‘Possibly,’ said Gabriella.

She showed me a third image: her, bleeding, in a bathtub. There was a gaping wound in her stomach. Her face was mournful.

‘That’s not fake,’ said Steph.

‘The thing inside of me, I would later learn, was The Thing called It that Žižek refers to. Das Ding in German. Slavoj has become a personal friend of mine.’ Gabriella smiled. ‘We met when I was invited to give a lecture on the King Cake project at the European Graduate School.’

‘Slavoj is a charlatan,’ said Steph.

‘He knows what I’m talking about,’ said Gabriella.

The fourth image showed Gabriella in a hospital bed.

‘I did some serious internal damage in the course of the project,’ she said. ‘I accidentally gave myself a hysterectomy. I couldn’t have children after that. I was only twenty-three at the time.’

Steph looked at me. ‘Your age,’ she said.

‘I had killed all my future foetuses for the sake of my art,’ said Gabriella. ‘Which seemed appropriate. Art is like giving birth, again and again. And putting your baby in an art gallery. Or a biennale.’ She held up the last image, which showed her looking pale and wan and much thinner in a wheelchair. ‘I never did find The Thing I was looking for,’ she said. ‘I’m still looking.’

&nbs

p; ‘Gabriella’s interest in surgery became multifarious from then on,’ said Steph.

‘The point is.’ Gabriella looked at me. ‘I don’t want to find It. If I found It, I would have no reason to make art any more.’ She got up and gripped her lower back. She produced another folder from the cabinet. ‘More recently, this is for the Venice show. It’s called Clamshell something. It’s going to have clamshell in the title.’

These images showed the various stages of a labiaplasty. First the distended asymmetrical labia minora was marked in purple ink. Then it was injected. Then it was cut off.

‘That’s when the cauterising kicks in,’ said Gabriella. She lit another cigarette. ‘Well, it’s very nice to meet you, Annie-Marie.’

I didn’t bother to correct her.

‘Those labials are just the crash-test dummy if you will,’ Gabriella went on. ‘One of my interns, very eager.’

‘You know it’s remarkable,’ said Steph. ‘Gabriella, you don’t need me to tell you that Orlan did this in the ’70s. She was cutting herself open way before plastic surgery became de rigueur. She was like a tribal woman, creating her own body. Still is, I should say. It was a beautiful moment when Orlan’s interventions chimed like music with Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto. But you—’

‘Are you trying to tell me I’m derivative, Mum?’ Gabriella laughed.

There was silence.

Finally Steph said: ‘I just think you could cite her.’

‘Was Orlan looking for Das Ding though?’ said Gabriella. ‘Did Orlan write as well? Was she a writer? Was Orlan looking for The Real, the bad part that must be exorcised from the living body in order for that body to go on living at all? Did Orlan know that unsaid words contaminate you from the inside out?’

‘No,’ said Steph. ‘All of that you learnt from me.’

‘Maybe I learnt it from you.’ Gabriella stood up. ‘But you only theorised that shit, Mum. You are a theorist. I did that shit. I did it to myself. The gravest acts of violence. The most pure – stitching my cunt up to make it look like a Barbie. That’s what I’m doing in the spring.’

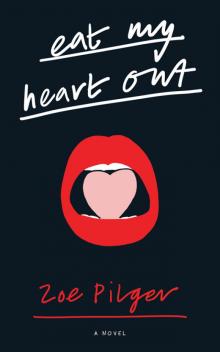

Eat My Heart Out

Eat My Heart Out