- Home

- Zoe Pilger

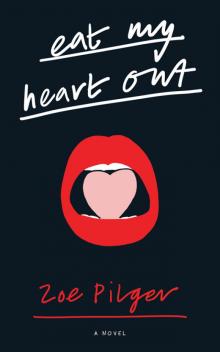

Eat My Heart Out Page 24

Eat My Heart Out Read online

Page 24

I was beginning to feel both dread and angst. There was my old pigeonhole, in which I had received numerous notifications that I was late, behind, wrong, bad, or just inadequate. In that hole, hand-scrawled letters from the Christian Society had begged to save my soul. I had been invited to audition for numerous Patrick Marber plays via that hole. It was in that hole that I finally received notification that I was no longer permitted to live in college accommodation.

The porters pretended not to recognise me.

Steph was making a fuss.

I sat on the long sofa that faced the pigeonholes and hyperventilated. Girls who looked stricken, traumatised, raped, weird, mad, old before their time, drifted past. Girls who had given up on men by the age of eighteen. Girls with death in their eyes. Girls with bunches at the age of eighteen. They were not ironic bunches; they were just bunches. The place reeked of arrested development and chronic perfectionism. The women-only college had begun to entropy sometime after its Second Wave zenith, when the admission of women to the university was still radical. But soon all the colleges admitted women. It was an atmosphere of despair.

‘Steph,’ I said, pulling at her sleeve. ‘Come on. Let’s go.’

Then Gabriella turned up. Once again, I was horrified by her appearance. Her technicolour blue eyes stared out.

The alumni coordinator – Simone, according to her name tag – had chaperoned Gabriella from the train station. Simone recognised Stephanie. She told her how much she loved her book, how much of a lifelong fan of her work she was. Simone castigated the porters for not rolling out the red carpet and said that of course she could find a place for Ms Haight and guest at the dinner that evening when Gabriella would be winning the Alumni Society’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

‘Gabriella’s winning it?’ I turned to Gabriella.

She nodded.

‘Did you go here?’ I asked her. ‘I thought Steph said you went to Goldsmiths – when Michael what’s-his-name was breaking every disciplinary boundary or something?’

Stephanie laughed riotously.

‘No, I never went to Goldsmiths,’ said Gabriella. ‘I was here at Cambridge – 1989 to ’92. I studied history of art. I always believed that the idea should come before the work of art so I went down the academic route!’

Simone the coordinator nodded.

‘I made the King Cake project straight after I graduated,’ said Gabriella.

Stephanie laughed more.

‘It’s embarrassing, really – to be honoured with a lifetime achievement,’ Gabriella went on. ‘I’ve not done much and I’m still only twenty-one!’

Now they all laughed.

Then Stephanie stopped laughing and said: ‘You were twenty-one the year the Berlin Wall came down, Gabriella.’

‘What’s that got to do with anything?’ Gabriella kept laughing.

Simone ushered us into a sterile room that I remembered well from the drinks reception that followed my nongraduation dinner. They must have sent the invitations out before the exam results were processed. I wasn’t going to go, but then I got stoned. I thought it would be funny. Allegra had been sitting over there, by the window. She was engaged in conversation with a quantum physicist. I hadn’t seen her since she fucked up my whole life. She pretended not to notice me. The coat of arms with the gold-plated ewe still hung on the wall. I stole a bottle of port from the drinks table, and she saw me do it. I went outside for a cigarette. She followed me. I told her to go away, but she didn’t go. I didn’t want to look at her so I looked to the left, at a hedge. Behind the hedge, there was a giant tin drum sculpture with a ball inside it that was supposed to represent the vulva. The ball was supposed to be the clitoris. We had laughed at it together, long before. She asked for a drag on my cigarette and I reminded her that she didn’t smoke. She asked for some of the port; I handed her the bottle. Soon we were passing it back and forth. She said something funny and I laughed. I can’t remember what she said. I remember how beautiful she looked and I remember thinking that she would always be more beautiful than me, and probably a lot nicer than me, and certainly a lot more charming. She was the better human being overall and Sebastian had been right to go with her. Then she went back inside.

‘I’m thrilled,’ Gabriella was saying, her face unmoving. ‘I just can’t tell you how fabulous it is for me to walk down memory lane.’

‘Ann-Marie came here too,’ said Steph.

‘We remember,’ said Simone the coordinator.

‘And I came here back in the dark ages too!’ said Steph. ‘So we’re all old gals together!’

‘I thought you went to St Anne’s in Oxford?’ I said. ‘That’s what it said on the blurb.’

‘Oh,’ said Steph. ‘The press always lie.’

‘But it wasn’t press,’ I said. ‘It was the blurb on your book.’

‘Steph forgets where she goes,’ said Gabriella.

I wanted to ask Gabriella if she’d ever been a life model, as Steph had said, but the gong was banged. It was dinner time.

There was the painting of the woman wearing the purdah, crouching in the desert with the Kalashnikov. It hung above the long table. The woman in the painting seemed to be pointing the Kalashnikov directly at the head of my former director of studies, Professor Kyle. He had sloping shoulders and watery eyes. His teeth were yellow, but all the girls fancied him because he was only about thirty-five. He had made a brilliant breakthrough on Karl Popper a few years ago, apparently. He too pretended not to recognise me.

Another gong was banged. Latin words were read out.

History of art undergrads had been selected for their virtue and seated near Gabriella. They had long hair and long legs. History of art alumni had been trooped in from all four corners of the earth, said the President, who was a quiet and judicious bluestocking. She had written me a decent enough reference when I applied for the job as door bitch at William’s. I watched the woman in the painting very closely, hoping she would fire.

The ravioli arrived – singular. When I pricked it, a yolk burst inside.

Steph put her hand up as though she were at school and called to the President: ‘Excuse me, is this free range?’

The President said that she was sure the produce was of the highest quality.

‘But is it free range?’ Steph demanded.

The President requested the presence of the chef. He too was an ex-policeman. He had started out at the college as a porter. ‘No,’ he told Steph. ‘It’s not free range, but it is local.’

‘So it’s from a local battery chicken farm?’

‘Stephanie,’ I said. ‘Leave it.’

The chef looked at me. ‘You’ve got a nerve,’ he said.

The main course was rose veal.

Steph began a tirade about how she wanted it tough. The chef was called again; he explained that he could only do justice to the veal if it was tender.

‘Then what is your job exactly?’ said Steph. ‘Because the yolk was raw and the meat is raw. What do you actually do back there?’

‘The chef makes everything wonderful,’ explained Simone the coordinator.

Between the veal and the lemon syllabub, the speeches began. A series of old girls stood up and described how they had successfully commandeered hedge funds and households and dogs and cats. They were living proof that women could really have it all, said the President. ‘And now please put your hands together for Gabriella—’ She listed Gabriella’s achievements.

Steph was holding a toothpick; I watched her dig it further into her thumb.

Gabriella thanked the authorities then held her hands up in self-defence at the Kalashnikov-wielding woman in the painting.

Everyone laughed.

‘I always did feel under surveillance and under threat,’ she said. ‘Here.’

Everyone stopped laughing.

‘I would love to say that it was all down to the fine feminist principles instilled in me by these white corridors,’ said Gabriella. ‘So redolent o

f Girl, Interrupted. Has any anyone seen that film?’

A few of the history of art undergrads nodded enthusiastically.

‘I bet you have.’ She laughed. ‘I wish I could say I transcended my immanence because of this place.’

Everyone waited.

‘But I can’t. We make art out of our pathologies as much as our strengths. This place ruined me – maybe I was already ruined. But the ruins gave me something to rise out of.’ Again, she laughed.

Stephanie laughed – too late.

Gabriella went on: ‘I might have been content instead of wanting to unstitch the very parts that held my soul together, to spread them out calmly, to see what was there. To see what was worth saving. And to see what urgently needed discarding.’

The President put her knife and fork together.

‘This place was the part that urgently needed discarding. One of many parts. It’s a shocking place, full of sexless pain. Full of the impotence of eunuchs. So it’s an irony to me that you wanted me back, possibly to claim my success as your own. Because I did it in spite of.’ She didn’t seem to be drunk. ‘This whole place is just like my father.’

‘And I eat men like air,’ added Steph.

I looked at Dr Kyle across the table and he looked right back at me.

Drinks were served in the college bar, which was not a bar but a youth club where no youths resided. Everything was purple and green and white – the colours of the suffragettes, as Steph pointed out. Simone said this was not intentional. The bar was sponsored by a budget airline because the Seven Sisters funding drip had dried up in recent years.

‘Yes.’ Steph nodded, earnestly. ‘Wellesley. Bryn Mawr. Vassar. Radcliffe—’

‘That’s right,’ said Simone. ‘They’ve all gone, mostly. They can’t support us any more. We’re the last all-women college in the country.’

‘He’s not a woman,’ said Steph, pointing at Dr Kyle, who was informing the bud-like breasts of a pretty undergrad about Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason.

Simone went to get more drinks. There was no bartender so she had to reach across the bar herself. Steph continued to stare at Dr Kyle.

‘He’s dangerous,’ she said. ‘He’s hot.’

‘Don’t.’ I made her look away. ‘I had a terrible experience with him in the spring. It was just before my exams. I wanted to seduce him so badly so I turned up to a supervision in a really short go-go skirt. I don’t know why I wanted to – because I hated him, probably.’

Steph nodded, furtively.

‘Maybe I wanted to seduce him because I wanted to seduce this whole institution.’ I gestured to the bar. ‘This whole place.’ I was tipsy. ‘Because if it was inside of me then it would approve of me. Maybe if I could make it come, if it had me on my knees then it would redeem the whole experience – somehow.’

‘Yes.’

‘It had ruffles – really nice ones. The skirt. It swished when I walked, and when I bent over, it rode all the way up. I thought about bending over his desk on the way to the faculty building. I did arrive on time, but then I bought a Mr Whippy at the last minute, and sat on the wall outside, and ate it, slowly. It took me a good ten minutes to eat it. The sun was shining – it was so hot. I thought I would be more mysterious, more sexy – making him wait. I didn’t have time to wash my hands, so my hands were sticky. I felt him recoil when I turned up at his door and offered my hand so that he was forced to shake it, but then he dropped it and told me I was late and so he was cancelling the supervision. He didn’t stand up. He said that I was in danger of never fulfilling my potential, and I said, still trying to be the coquette: But what potential can you mean, Professor? He told me that I should leave his office. Really? I said. Yes, he said. I told him that I wanted to overcome myself in order to become myself – or become anything at all. But he just turned back to his computer.’ I took Steph’s hand. ‘I was nothing at the time.’ Her hand was limp and damp. ‘You have to understand that I was nothing.’ I too was sweating. I could see Gabriella sweating across the room. ‘I was nothing.’

‘Yes,’ said Stephanie.

‘When I went next door to get some bureaucratic form or other, the secretary told me that I had white stuff around my mouth. I went to the toilet. I looked in the mirror. It was the ice cream.’

There was no way the porters would trust me with keys to any room, so Gabriella told them that it was she and not I who wished to see the seminar suite. She said she wanted to reminisce in there.

‘Yeah,’ I said, closing the door behind us. ‘This was where they made me come and sit the rest of my exams after I walked out of the first one. They wouldn’t let me back in the main exam hall after all that screaming.’

‘Why did you walk out?’ said Steph.

Tubes of light ran around the ceiling; the room was bare. We were all very drunk.

‘I ran out of time,’ I said. ‘There was no more time. I was supposed to be writing, but I was thinking about Dr Kyle. I thought about Dr Kyle. I thought about how Dr Kyle would never fail – or fuck me. It was the pressure. I’d had it up to the eyeballs.’ I laughed. ‘But they stopped the clock. They put me in here.’ I moved to the back of the room. ‘I was alone. Except for the invigilator and this one other girl. Bizarrely, she was called Mary-Anne. Which is almost my name, backwards. She sat at the back. Here.’ I stared at the whiteboard from where Mary-Anne had sat. ‘She was doing engineering. She had a twitching jaw and, every time I came in, she did this demented thumbs up. After the second or third exam, I came to welcome her thumbs up.’

Stephanie picked up a marker pen. She was about to write something on the whiteboard, but then she changed her mind. She put the pen down. Very slowly, she said: ‘It’s a disgrace.’

‘So they segregated you,’ said Gabriella. ‘They quarantined you because you wouldn’t conform.’

‘Well, they said I was a threat to the ability of my fellow exam candidates to concentrate. They said I would be better off in here.’

‘So you passed?’ said Gabriella. ‘You passed?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘I failed.’

It was hours later. The sun hadn’t yet come up over the red star of the Texaco garage across the road, but soon it would illuminate us, illuminate Castle Mound just beyond, where Allegra had staged her communion with the elements and failed to feel anything at all. Soon the signs to keep off the grass would be illuminated too, and soon the rowers would start rowing, and the earth would keep turning. But for now it was dark, except for that weak red light across the road, making the face of my director of studies, Professor Henry Kyle BA (Oxon) MPhil (Cantab) PhD (Cantab) look sorry.

‘Please forgive me for being so powerful,’ I was saying, as Gabriella and Stephanie danced around the room to the ringtone on Gabriella’s phone: ‘What Difference Does It Make?’ by The Smiths.

Dr Kyle couldn’t respond because he was gagged. He was bound with the standard issue bed sheets that the cleaner had diligently left folded in the wardrobe.

We had bumped into Dr Kyle on the way back to the bar from the seminar suite. He had been photocopying handouts in the admin corridor, drunk.

This had been my room. I hated it.

Dr Kyle twisted from side to side.

‘It’s the overhead light or darkness,’ I told him. ‘Because there’s no bulb in the sidelight. Someone forgot to change the bulb.’

He twisted more.

‘Do you want to see what is happening to you?’ I said.

He nodded. Then he shook his head.

Gabriella and Stephanie held hands and formed a ring. There wasn’t much space between the bed and the desk. Steph kept banging into the desk chair. We had got his trousers and his boxer shorts round his ankles but his shoes wouldn’t come off. I pulled and pulled, attending to each foot. Finally, the first one gave. I fell against the wall. The second one gave more easily. I unbuttoned his shirt.

Gabriella was explaining that she was an amateur surgeon in the eighteenth-century tradi

tion. At that time, women were only entitled to be amateurs, but they took their work extremely seriously. She talked about the difference between the scatological and sentimental in contemporary art. Then she got out her surgical travel kit.

‘Are you listening?’ she asked Dr Kyle.

He nodded. He was trying to recoil but the sheets were bound too tightly.

Gabriella sat down on the edge of the bed. She lit a cigarette.

I fixed one of Dr Kyle’s socks over the smoke alarm.

‘Do you include a module on doomed romantic love in your social and political science syllabus?’ said Steph. She lit her cigarette off Gabriella’s.

The professor was trying to breathe.

‘Well, do you?’ said Stephanie.

‘No,’ I said. ‘They don’t.’

‘Do you plan to include one?’ said Steph.

He nodded, frantically.

‘Because let me tell you.’ Steph wafted her smoke around the room so that it curled in the shadows. ‘It’s really a key aspect of human culture that has been neglected by the humanities of a quasi-scientific bent. Those who have pretensions to empiricism.’ She stood over him. Then she sat down next to him.

His sweat had soaked the bed.

‘The rise of the individual has coincided with the invention of romantic love as we know it. It’s all about free choice.’ Steph laughed.

Gabriella laughed too.

His eyes looked stricken.

Steph moved around the glass partition separating the bed from the sink. I saw her double-glazed form bend over the rushing tap. She returned. ‘Like if we think of the myths. Tristan and Isolde, Romeo and Juliet, Heloise and Abelard. They all experienced a preternatural feeling of truth in relation to the other, a purity so deep that they would prefer to be together in death than apart in life. Isn’t that right, Ann-Marie?’

‘Yeah.’ I told Dr Kyle: ‘It was really humiliating that time with the ice cream.’

‘The latter is a particularly fascinating case study,’ Steph went on. ‘Abelard was a brilliant man. A scholar. Heloise was brilliant too. He taught her. But then her father got mad, as fathers tend to do.’

Eat My Heart Out

Eat My Heart Out