- Home

- Zoe Pilger

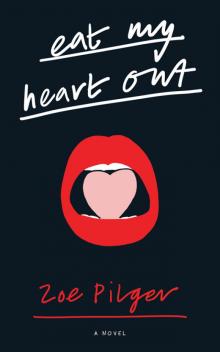

Eat My Heart Out Page 8

Eat My Heart Out Read online

Page 8

I located Stephanie’s house on the map and got on the tube to Camden.

An hour later, I was standing outside Stephanie’s house in Camden Square, reading the torn tributes to Amy stuck on that tree. Someone had left a can of Stella at the base, along with a candle. A polka-dot ribbon had snagged in the branches of a nearby bush.

Nothing was growing.

An Anglo-American voice said behind me: ‘It’s so nice of you to leave those. Most people have stopped.’

I was holding a bunch of pink carnations.

Stephanie stood before me.

She had a dog on a lead. She nodded at the flowers. ‘We welcome mourners.’

‘Oh,’ I said. I was nervous. ‘No. These are for you.’

We were sitting at Stephanie’s big wooden kitchen table. It was mahogany, she told me. I was dazzled.

There was another mannequin, which had been moved out of the lifestyle photographer’s shot. ‘I wanted to keep her all to myself,’ Stephanie was saying, sipping her Java Deluxe. The mannequin was bent down on all fours. A leather cushion was strapped to her back. ‘I wanted to keep her private, safe. It’s silly, really.’ She scrunched up her nose and shook her head.

I heard myself saying: ‘No. It’s not silly at all. I know exactly what you mean.’

‘You do?’

The house was cavernous and comfortable. The central heating was turned up high. There was a feeling of calm.

‘Well,’ I said. ‘Only in my small way. My flatmate Freddie and I made a series of films in the summer – of different women writers, committing suicide.’

Her eyes widened. ‘How fascinating. Why?’

‘It was Freddie’s idea. I think he admires tragic women. He likes to watch women die.’

‘Is he a queen?’

‘Yeah – if that’s an empowered word.’

‘Queens can be just as oppressive as normal men.’

I laughed, nervously. ‘Surely there’s no such thing as normal?’

‘Oh, but there is.’ She blew on her coffee. ‘Go on.’

‘I guess he got the idea from me because I was always going on about how there are no strong women role models, you know? No one who we want to aspire to.’ I reddened. ‘Apart from you, of course.’

Now we were wandering around the edge of her swimming pool, downstairs in the basement. Stephanie had commissioned an architect from LA to design the house. Faint pink light fell over the water from an obscure source. The ladder sparkled in the light. The drains sparkled. The walls were painted chlorine-blue to match the water.

Our voices echoed.

‘And how did you feel – playing the victim?’ she asked me.

‘I don’t really see those women as victims.’ I watched our shadows fall across the water. We were the same height. ‘I just see them as victims of circumstance, I guess. I don’t know. I don’t really have the words – to say what I mean.’

‘Without language, the rebels can only eat themselves,’ said Stephanie. ‘Or something like that. That’s Acker. Have you read her?’

I shook my head.

‘Oh, you must. Blood and Guts in High School is a classic of the underground. She’s much better known in the States than she is over here.’ Silence. ‘She had a double mastectomy, you know.’

I stared at her.

Stephanie moved to the other side of the pool. There was a door.

We entered a gym.

‘The shoulder press is still being put together,’ she explained.

There was dust everywhere.

‘I’m a big fan of the cross-trainer,’ I said, dumbly.

Stephanie ran her hand over the levers. ‘Well, you can use this one whenever you want.’

Now we were sitting on her roof terrace, wrapped in matching Afghan rugs, heated by electric suns, or so it seemed to me. We watched the mist rise over Camden Square.

‘Maybe I’ll move back to North London soon,’ I said. ‘I’m from here.’

‘Oh?’ She took out a packet of Gauloises and offered me one.

We smoked together in silence.

‘I’m from South London.’ She exhaled.

I exhaled. I watched her mouth.

‘Bermondsey,’ she said. ‘I was born above a sweet shop that later turned into a hardware shop.’ She laughed. ‘DIY shop. That comes from years of living in the States.’

I waited.

‘My family were poor. White trash, they’d be called over there. It was just me, my mother, my father, and brother in two rooms. Man, it was tough. That’s why I ate. Yes. I used to be a fatty.’

There was a pause, and then we both laughed.

‘I ate and ate and ate because I was depressed,’ she said. ‘Because I was smart. Clever. And I was a girl.’ She tutted. ‘Not a good combination. You must have read Gatsby.’

‘A long time ago.’

She fetched a Tiffany ashtray. ‘You know when Daisy has a baby and she finds out it’s a girl? She says – Well then she’d better be a perfect little fool.’

My heart was thrashing.

‘I wasn’t a fool,’ said Stephanie.

We were in her study.

Stephanie had asked me to type falling into YouTube. She was leaning over my shoulder and I was sitting in a teak swivel chair, overlooking the garden.

‘Now see what we get,’ she said. ‘Songs about falling in love. A song called ‘Falling’ by Florence and the Machine. There!’ She pointed to a video titled Beautiful Girls Falling.

We watched a procession of models with stick-legs attempt to make it down the catwalk. Their shoes towered. Each one tripped, stumbled, fell onto her fragile knees. The shot replayed: trip, stumble, fall.

‘Precipices.’ She reached over me. I could smell her perfume: dead oranges on a hot day. It was too tart. ‘Here.’ She found a clip of the glamorous Tallulah Bankhead reading an excerpt from Dorothy Parker’s short story ‘A Telephone Call’. We listened to the incantation, the gravelly voice, the rising delirium of a woman who simply waits. She waits by the phone for her lover to call. She waits because she can only wait, because for a woman to be active and just pick up the goddamn phone and call the man herself at the time that Parker wrote the story – 1928 – was to be deemed a predator.

‘Or worse,’ said Stephanie. She turned the computer off. ‘I’ve had that all my life.’ She stood behind me. ‘I can see it in your eyes that you’re going through the same pain that I went through.’

‘I’m not fat,’ I said.

‘No,’ she said, irritably. ‘I mean when I was older. After I’d graduated. I was thin by then.’

I could see her looming in the reflection of the blank screen.

‘There was a reason that you came to this house,’ she said. ‘There was a reason that you found me.’

‘What was the reason?’

‘Can’t you see?’ Stephanie laughed joyfully. ‘Can’t you see?’

After a moment, I laughed along with her. Then I said: ‘See what?’

‘This is the call. This is the call you’ve been waiting for.’

We were in the bedroom. It was lined with books. The curtains were red velvet, brand new. The walls were a stark, unforgiving white. A rich red rug was spread on the wooden floorboards.

‘I wanted a red room,’ she said. ‘But I didn’t have the courage to go all the way.’

‘Like Christian’s Red Room of Pain in Fifty Shades?’

‘Have you read it?’

‘Yes – well, only because Madeline, the head waitress, left it lying around reception. I read it during my shifts. I would never have read it otherwise.’

‘Did you like it?’

‘No?’ I watched her face to see if this was the right answer. ‘It gave me nightmares. The violence. I hated Anastasia’s – submissiveness?’

‘Quite.’ Now she looked angry. ‘That book is poison. Pure toxic poison. It is fortuitous that Falling Out of Fate coincided more or less with that … trash.’ Her face becam

e normal again. ‘I wanted this room to be like the red room of Jane Eyre’s childhood. Where she goes as a little girl – or rather, where she gets locked inside. There she has visions. She has hysteria. Hysteria is the corralling of women’s natural jouissance under patriarchy.’

‘Yeah, I met this guy,’ I said, excitedly. ‘In the restaurant last night—’

‘Yes,’ she hissed. ‘Yes. That is where I saw you.’

I reddened.

‘The restaurant that serves the delicious rabbit,’ she said. ‘That is where you read Fifty Shades?’

I nodded. ‘I didn’t want to say I saw you there. In case you thought … I was stalking you. I took this.’ I pulled her book out of my handbag. ‘It was meant for your friend?’

We were sitting on the bed.

‘Oh. Marge.’ Stephanie rolled her eyes. ‘Marge has been through a very bad divorce. Her ex-husband is English, of Chilean descent. And you know what Latin men are like, notoriously.’ She leaned back and rested on her elbows. ‘Luckily I have exorcised all the superstition out of myself, Ann-Marie. Otherwise I would think that you and I meeting was a perfect instance of fate.’

Now she led me to the landing on the third floor. The lamp above was a Chinese paper dragon. There was a stone sculpture – a woman sitting in a rocking chair.

‘This,’ said Steph. ‘Is Penelope.’

The stone woman was gripping a stone garment. She was knitting.

‘Don’t you know who Penelope is?’ said Steph.

‘I can’t remember.’ I blushed.

‘She is the lover of Odysseus!! She waits for him for years and years!! She waits by the window!’ Stephanie gripped the stone woman’s shoulder. ‘She wove and wove to put off her suitors because she believed in her heart of hearts against all common sense that Odysseus would come back for her. If she finished the thing she was weaving, if she ever dared to complete her labour, she would have to betray him. To complete her own work was to betray her man. Do you know what that means?’ Steph bowed her head. ‘So she unravelled every night what she had done every day. She never owned it.’

‘What happened?’

‘He came back. They were happy. Then there were other complications – you know, people turning into animals, sleeping with their mothers.’

‘I’m sorry.’ I blushed again. ‘I never had a classical education. I went to a comprehensive.’

Stephanie’s eyes glimmered. ‘Me too! They were called secondary moderns in those days!!’ Now she was twirling me round and round on the landing.

We had returned to the swimming pool.

Steph was slipping into a bright red bikini. She had tossed me a bright green bikini.

I was hoping that she would point me in the direction of a changing room. To ask for privacy now would be tantamount to a mythological betrayal.

‘Oh, screw it,’ she said, and ripped off her bikini. Her body was smooth. I could detect some incisions under her arms and around her buttocks. She dived into the pool.

I was hoping she would stay underwater for a minute and let me change, but she bobbed, staring at me. I took off my clothes and put on the bikini.

I eased myself into the water.

Steph swam towards me.

‘Every woman who wants to come into consciousness of her being must become a mythographer,’ she was saying. ‘Every woman who wants to understand why she does what she does. Why she is so fucked up.’

‘I’m not fucked up,’ I said.

She laughed.

‘No,’ I said. ‘I’m really not.’

‘How could you not be?’ She kept laughing. ‘You are subject to normative femininity, which is a perversion. You are a perversion.’ She ducked underwater.

When she resurfaced, she said: ‘The antidote to the snakebite is.’ She ducked again. She was making me chase her down to the other end of the pool. She launched her shimmering body onto the side. ‘You must make your own myth. Make a myth of yourself. That’s what I did.’

Later, wrapped in towels, we were sitting on loungers by the pool and drinking double Jameson’s on ice because Steph said it reminded her of her New York days. I was telling her about Samuel and how he desperately wanted to be from Williamsburg. ‘Why?’ she groaned. ‘What’s interesting about self-regarding hipsters with nothing to say?’

I told her about Samuel’s fixation with The Little Mermaid.

She got excited. ‘Read a chapter called “The Woman in Love” in The Second Sex by de Beauvoir. Have you read it?’

I shook my head.

‘You must,’ she said. ‘She talks about why love shouldn’t be sacrifice. Because the mermaid sacrifices her tail for legs and leaves everything behind. But when she goes on land, she feels there are hot knives stabbing into the soles of her feet with every step that she takes. It is torture.’

‘But they’re happy in the end?’ I said, dumbly. ‘Her and Eric?’

‘Who’s Eric?’ laughed Steph. ‘I’m talking about the original, the Hans Christian Andersen version. There’s no Eric. The prince falls in love with someone else. He rejects the mermaid. And then she dies.’

Steph and I were back in the kitchen.

The front door opened. There was the sound of a child, an American. The prim ballerina from the restaurant appeared, along with Marge Perez. They were weighed down with bags.

‘Oh,’ said Marge. She held her key aloft, as though ready to open another door. ‘You have a visitor.’

Steph stood up. ‘Don’t be like that, Marge. How was shopping? Get everything you need?’

‘Yeah!’ chirruped ballerina. She pulled out a packet of marshmallows.

Marge sat down heavily at the breakfast bar and said to me: ‘So. Are you seduced?’

Eight

Stephanie had promised that I could return, soon.

It was Sunday night. I had relented and gone to Samuel’s party at the peanut factory in Hackney Wick. My poetry slot was at 11.30.

From the podium, I read to a crowd of fools dressed like creatures from the deep:

‘I can’t love you if you kill me.

Lover, I am ransacked.’

Freddie and Samuel waited for me to continue.

‘That’s it,’ I said into the microphone. It screeched – an amplified gull.

Mirages of mermaids flew across the room. The crowd ignored my poem and continued to dance to no music.

Freddie looked at Samuel, who shrugged. He fiddled with his decks. The noise returned: Siren, siren, siren SONG.

I got out of the papier-mâché seashell, climbed down from the podium, and pushed through people and pissstained corridors until I found an exit. It opened onto a back alley. There was a rotting mattress, a green dreadlock. A giant cartoon peanut waved to me from the roof. Its white-gloved hand looked like a cloud against the black sky.

Freddie appeared. ‘What the fuck was that?!’

‘I’m sorry.’ I lit a cigarette. ‘I couldn’t think of any mermaidthemed stuff at the last minute so I just used something old. Do you remember when I wrote that poem?’

‘Your self-obsession is no longer amusing,’ said Freddie. ‘It’s become vulgar.’

‘Freddie, when you’ve done loads of drugs you look like a frightened horse.’

‘How sweet.’ He attempted to run up the brick wall, which didn’t work. He crouched before me. ‘Why don’t you write a poem like that for me?’

I stared at him.

He stood up and brushed his harem pants. His face was smeared with blue. ‘That wasn’t even a poem, anyway,’ he said. ‘That wasn’t even a haiku. That was more like a song lyric. A fucking schmaltzy R&B song lyric that I have to hear whining out from behind your bedroom door every time you fuck some random who never calls you.’ He shouted in my face: ‘I always call you!’

‘I don’t want to be called by you, Freddie,’ I said. ‘We live together. You don’t have to call me.’

‘Well, I’m going to call you.’ He pointed to me and staggered

against the wall. He snorted something off his key. He offered me some.

I shook my head.

‘You know what you are,’ he said. ‘Sentimental. You believe in the soul. When I told you a million times that there is no such thing as the soul.’

I looked at the sky; three stars were aligned.

Freddie grabbed the front of my vintage shoulder-padded ’80s black leather jacket and sneered: ‘Life is a constant process of decay.’

‘No, Freddie. Life is a constant process of becoming. Nietzsche—’

‘Oh, fuck Nietzsche!’ He disappeared into the peanut factory.

I checked my phone: twenty-eight messages. It was an unknown number.

Hey bunny-boiling bitch, where are you?

You said you wanted to fuck me, now where the fuck are you?

You thought you could turn me on with your hamster-boiling stories and then leave me for dead?

Are you going to leave me?

If you don’t tell me where you are, I’ll hunt you down and spit-roast you like that fucking sow.

Like the sow that you are.

Vic!

I texted him the address of the peanut factory and told him to come right over. I headed to the toilet to freshen up.

It was a sea of shit. Brown footprints ran in circles on the floor. Hipsters of every sub-genre were skating all over the place, grabbing at each other’s sewn-on fish scales. The cubicles had no doors. I reapplied my Pleasure Me Red lipstick, fighting for space in front of the broken mirror.

A girl wearing a blue sheer tube-dress buckled in her wedges. She tried to drag me down backwards, but I clung onto the grimy sink, supporting her weight as well as my own. Another girl barged into the room wearing a toga the colour of a miniature golf course. It was draped over one breast and one shoulder so that her other breast stared out at everyone. This girl was painted green. Her face was green. Her hair was a tangle of green dreadlocks. She hauled the tube-dress girl into a standing position, then leapt onto the sink. She squatted over it and hoisted up her green billowing skirts to reveal no underwear. ‘Look!’ she shouted.

The room turned to stare.

She prised open the lips of her vagina to reveal a deep pink interior. ‘There’s an alien waiting to crawl out of me!! Yep! That’s right! I’m pregnant!’

Eat My Heart Out

Eat My Heart Out